Your Post Is Competent, Forgettable, and Slowly Dying

AI didn’t make your writing worse. It made your writing invisible. There’s a name for the thing that’s killing it.

My first Voiceprint client was a fitness creator named Dana. She’d been publishing three newsletters a week for two years, building a loyal audience of around 8,000 subscribers. She had this ability to turn gym failures into life lessons, and her readers loved the way she made even a bad workout feel like a small act of defiance.

She came to me because she’d started using AI to co-write her drafts and something felt “off.” She couldn’t name it. Her quality hadn’t dropped. Her structure had actually improved. But her open rates were quietly declining, and the replies that used to flood in after every post had slowed to a trickle.

I found the problem in her first three paragraphs.

That story is a fabrication. Total BS. All of it.

No Dana. No fitness newsletter. No 8,000 subscribers. No gym-failure life lessons. I gave AI a prompt, it generated that opening, and you read the whole thing without your brain raising a single red flag. The details felt plausible. The emotional arc tracked. The subscriber count was specific enough to seem real. Everything about it pattern-matched to “authentic personal anecdote” and your internal security waved it through without checking ID.

(And if you’re thinking “I knew something was off,” no you didn’t. You kept reading. That’s what “off” looks like when the faking is competent: a passing thought you immediately dismiss because the next sentence is already pulling you forward. The bouncers at this club are glancing at IDs and nodding people through, and the fakes are coming from a guy who got fired from the DMV last Tuesday and took the laminator with him.)

Here’s what matters about that paragraph, though, and it’s not the dishonesty.

It was adequate. Serviceable. The kind of perfectly fine opening you’d read in any of the forty-something newsletters sitting in your inbox right now. And if I’d kept going (if the whole post had been built on AI-generated anecdotes and borrowed opinions and fabricated client stories), you would have finished reading, thought “that was pretty good,” closed the tab, and retained absolutely nothing by Monday.

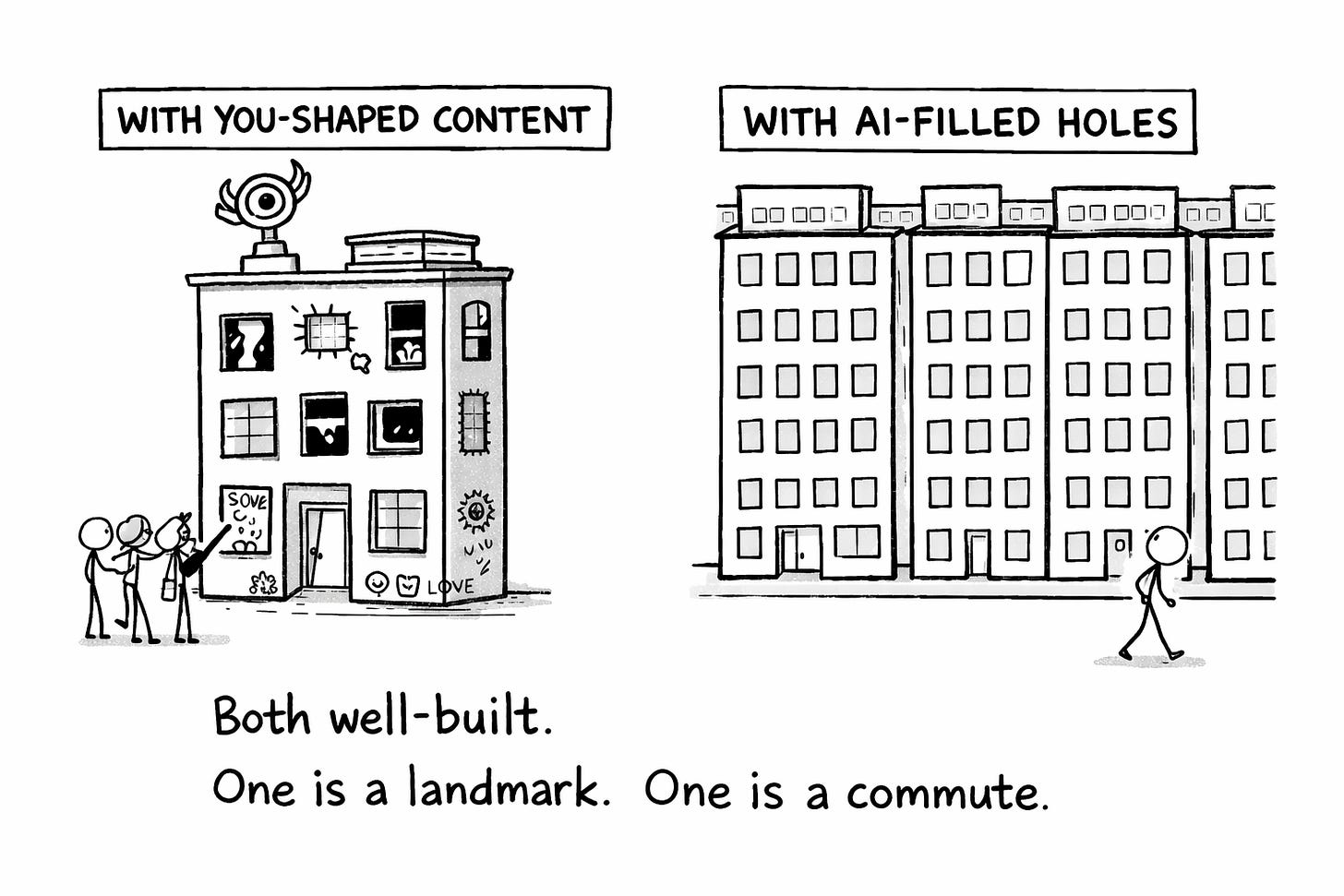

Not because you’re inattentive. Because there was nothing in it designed to survive the trip from your screen to your memory. No image weird enough to lodge sideways in your brain. No opinion sharp enough to make you argue with your phone. No moment where you thought only this specific human would have said it exactly that way.

The Dana paragraph was a you-shaped hole. A spot where a real story from a real life should have been. And AI filled it the way AI always fills them: smoothly, confidently, and with the lasting impact of a sneeze in a hurricane.

This is Part 1 of a 3-part series on you-shaped holes, the most dangerous blind spot in AI-assisted writing.

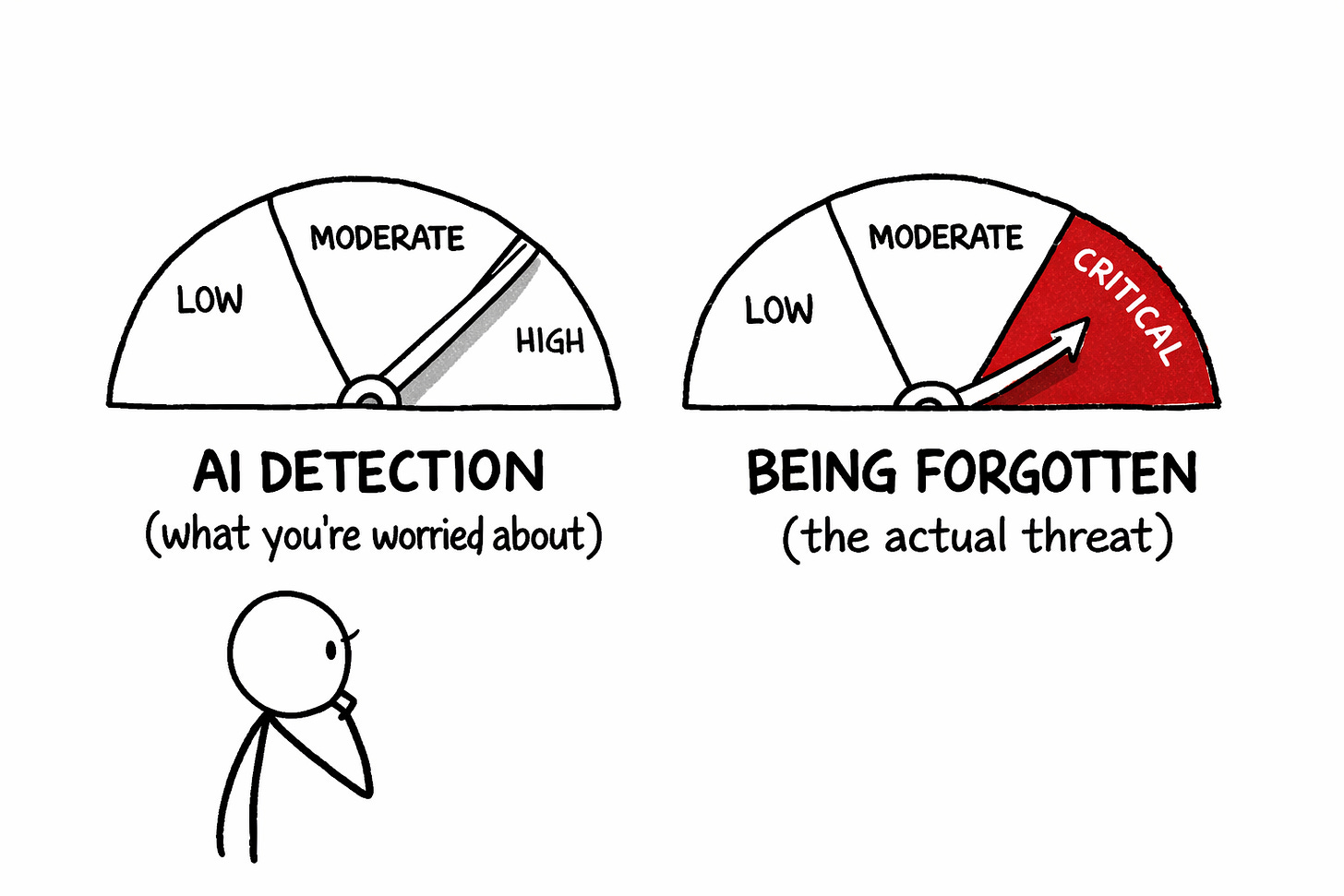

The Wrong Threat (And Why You’re Guarding the Wrong Door)

Everyone in the AI writing conversation is panicking about the wrong thing.

The fear is that AI makes you sound robotic. Stiff. Corporate. That your readers will detect the AI and lose respect for you. So creators obsess over making AI output sound “natural” and “human” and “authentic,” and the entire cottage industry of AI writing advice is basically: here’s how to make the machine sound less like a machine.

Which is adorable, because the machine already figured that out on its own.

AI doesn’t sound robotic anymore. Not if you give it half-decent instructions. The outputs are fluent, conversational, correctly punctuated, appropriately toned. They pass the sniff test. Your readers aren’t sitting there with AI detectors and suspicion. They’re reading your post on their phone while waiting for coffee, and the writing is fine.

That’s the real threat. Not bad writing. Fine writing.

Fine writing that sounds like it could have come from any of the twelve other newsletters in your niche that also use AI with half-decent instructions. Fine writing where the “personal stories” are composites, the “opinions” are consensus positions stated in first person, and the “examples from my work” are statistical averages wearing a trench coat and pretending to be a specific human being’s actual Tuesday.

Your readers aren’t going to catch your AI. They’re going to forget your newsletter. And they won’t even notice the forgetting, because forgetting something unremarkable doesn’t feel like anything. It’s the absence of a feeling. A non-event. The newsletter equivalent of a stranger’s face on the subway: technically perceived, immediately overwritten, gone before the next stop.

What Memory Actually Grabs Onto (And What Slides Right Off)

Think about the newsletters you’d genuinely miss if they vanished. Not the ones you “should” read. The ones that, if they stopped showing up, would leave a hole in your week.

You can name particular moments from them. The time that one writer described her kid announcing “mommy's pooping” during a podcast interview and turned it into a piece about radical transparency in brand building that actually made you rethink your about page. The guy who opened a post about SEO with a three-paragraph confession about crying in an Arby's bathroom stall after his first site got deindexed. The woman who called sales funnels “Rube Goldberg machines that occasionally spit out a customer” and you laughed so hard you sent it to four people

Those moments aren't better written than the rest of the post. You just can't imagine anyone else writing them. They contain details that could only exist because one particular person lived one particular life and chose to put that weird, uncomfortable, sometimes-embarrassing detail on the page.

Now think about the newsletters you technically subscribe to but couldn’t describe to a stranger. You know the ones. They show up. You open them (sometimes). The writing is solid. The advice is sound. And if someone asked you “what’s that newsletter about?” you’d say something vague like “AI writing tips” or “marketing strategy” because nothing sharp enough to name has ever lodged in your memory.

The difference between those two categories is almost never talent. It’s almost never “quality of writing.” It’s the presence or absence of you-shaped content. Material that could only have come from one particular human. Details that resist averaging. Moments that stick in your brain because they’re too weird, too personal, too real to get flushed down the same drain as the eleven other newsletters your reader opened and immediately forgot that morning.

AI cannot generate any of this. Not because AI is bad at writing. Because AI has never cried in an Arby's bathroom stall, had a kid blow up its podcast interview, or described its own sales funnel with enough self-loathing to make strangers laugh. It generates the statistical average of all experiences, which is the definitional opposite of memorable. It's the mean. And the mean is exactly where you go to be forgotten.

Three Ways AI Makes You Disappear

You-shaped holes come in three varieties, and each one erodes your memorability in a different direction.

1. The Fabricated Experience

AI writes a story you didn’t live. Like our friend Dana. Perfectly structured, emotionally appropriate, and destined for the same psychological landfill as every other plausible-but-generic anecdote your reader encountered this week.

A real story from your actual life carries grit. Strange details. The kind of texture that makes a reader think “that’s too weird to be made up.” Your real client wasn't a fitness creator with a clean narrative arc. Your real client was a bookkeeper who wrote a Substack about debt management and went quiet on your second call when he realized he'd never once mentioned he was $340,000 in debt himself. Every post about “building financial discipline” written at 2 AM from a living room he was three months from losing. Two years of authority content from a man drowning in the exact problem he was teaching people to solve, and not one reader knew, because every post read like it was written by someone who had their life figured out. Because AI made sure it sounded that way.

(Or it happened to someone. I just made that up too. But notice how much more it stuck than Dana’s story. The bookkeeper $340,000 in debt writing about financial discipline at 2 AM. You’ll carry that image tomorrow. You’ve already forgotten what sport Dana coached. Specificity is a memory anchor. Plausibility is a memory ghost.)

2. The Borrowed Opinion

AI states a position as yours that you’ve never held. It finds the consensus view of your niche and deposits it in your newsletter in first person. The result is the opinion equivalent of saying ‘thoughts and prayers” after a disaster: all the vocabulary of caring, none of the weight, and everyone involved quietly knows it.

Your readers don’t retain consensus. They retain friction. The take that made them pause. The position that was almost too strong. The moment where you said something they hadn’t considered and they felt their brain physically reorganize around a new idea. (Or the moment where they violently disagreed with you and read the whole post anyway because they needed to know how wrong you were going to be.)

Borrowed opinions create neither reaction. They slide through the reader’s brain like a greased marble through a tube. Frictionless. Forgettable. Functional.

3. The Generic Example

AI fabricates “a client I worked with” or “a creator I know” scenarios that are plausible but connected to nothing real. These are the slow poison. One generic example is harmless. Two is a pattern. Ten across five posts and your newsletter reads like a Wikipedia article that somehow scored a Mailchimp account.

Your readers can smell the difference between “a creator I worked with who struggled with consistency” and “my client Sarah who texted me at midnight on a Monday because she’d accidentally published a half-finished draft to 4,000 people and wanted to know if it was too late to rebrand as a mysterious avant-garde newsletter.” One of those is information. The other is a story someone tells at a dinner party. Guess which one your reader is still thinking about when they open your next email.

The Arithmetic of Disappearing

One you-shaped hole per post doesn’t kill you. You barely notice. The paragraph works. The draft ships. Nobody complains.

But the math doesn’t care about individual posts.

One hole per post. Two posts a week. A year of publishing. That’s a hundred-plus spots where a moment your reader would have carried with them got replaced by adequate filler they won’t. A hundred chances to be the newsletter they quote to a friend, converted into a hundred instances of professional-grade filler.

After twelve months, your archive is clean, well-structured, properly formatted, and contains approximately zero moments that any subscriber could name if you put a gun to their inbox. (Metaphorically. Please don’t threaten inboxes.) You’re publishing regularly. Your craft is solid. And you’re being outperformed, in terms of reader loyalty and retention, by a creator with half your skill who peppers every post with real stories, controversial takes, and the kind of details that stick to the inside of your skull like gum on a shoe.

They’re not better than you. They’re just more present in their own work. Their fingerprints are on every page. Yours were quietly replaced, one paragraph at a time, by the most probable version of what someone in your niche would write. And “most probable” is a fancy way of saying “interchangeable with everyone else doing the same thing.”

(The darkest version of this: you’ll know it’s happening when a reader replies to someone else’s newsletter saying “this reminds me of something I read somewhere” and they’re half-remembering your post but attributing it to the wrong person. Because your version didn’t have enough of you in it to pin the memory to your name. Your ideas, rehomed. Your argument, attributed to a stranger. Your work, orphaned by your own anonymity. The tax on forgettable.)

The Memorability Audit (Start Here, Start Now)

The fix begins with a question you’ve probably never asked your own drafts.

After your next AI-assisted piece, read it once for quality. Flow, argument, structure. Normal editing.

Then read it again with this filter:

“Would my reader remember this part next Thursday?”

Not “is this good?” Not “does this flow?” Not “would this pass an AI detector?” The question is: if your reader is describing your newsletter to a friend over drinks next weekend, would this paragraph be part of the description? Or would it dissolve into the vague impression of “it was a good newsletter about [topic]”?

Run every anecdote through it. Every opinion. Every example. If the answer is “this could have appeared in any newsletter covering the same topic,” you’re looking at a you-shaped hole. AI filled it. The filling was smooth. And it will evaporate from your reader’s consciousness like morning fog off a parking lot.

The first time you run this audit, the results will sting. Not because your writing is bad. Because you’ll realize how much of it is adequate. Adequate and forgettable. Adequate and interchangeable. Adequate and slowly eroding the only competitive advantage you have in an inbox of forty-something other newsletters: the fact that you’re a particular human with a particular life who says things in a way that nobody else would.

(I ran this on my own archive when I first developed the framework. Across two months of posts, roughly a third of my “personal examples” were AI-generated composites I’d waved through during editing. Every one of them read well. Not a single one was the kind of thing a reader had ever quoted back to me in a reply. The stuff they quoted? Always the real stories. Always the weird details. Always the parts I’d been embarrassed to include and almost deleted. The stuff AI contributed was structurally pristine and spiritually dead on arrival.)

That uncomfortable audit is where better co-writing begins. Because once you see the holes, you can stop AI from filling them with polished turds. You can fill them yourself, with the material that actually makes your work stick.

Which is exactly what Part 2 covers: how to train AI to flag you-shaped holes instead of filling them with filler your readers won’t carry past lunch. The behavioral shift that changes everything about how your drafts get built.

🧉 Be honest: have you ever forwarded a newsletter to someone and said “you have to read this'“? What was it and what made you hit send? I think your answer may reveal exactly what memorable actually means better than anything I wrote above.

Crafted with love (and AI),

Nick “Forgettable Newsletter Eulogist” Quick

PS… If this post just made you want to forensic-audit every newsletter you’ve shipped in the last six months (sorry, also you’re welcome), there’s more where this came from. I publish daily. Frameworks for co-writing with AI without slowly becoming the newsletter equivalent of a hotel room painting nobody’s ever taken a photo of. Subscribe if you’d rather be the painting people photograph and send to three friends. And if you know a creator whose newsletters you technically receive but could not describe a single thing about? Forward this. Not as an insult. As a rescue operation. They’ll figure out which one it was later.

PPS… That memorability gap gets worse when AI is guessing at your style and your substance simultaneously. The Voiceprint Quick-Start Guide walks you through documenting your VAST patterns (Vocabulary, Architecture, Stance, Tempo) so AI at least stops improvising how you write and you can focus on catching what it fakes. One problem at a time.

📌 The You-Shaped Holes Series:

→ Part 1: Your Post Is Competent, Forgettable, and Slowly Dying ← You are here

→ Part 2: I Trained My AI to Say "I Don't Know" and My Readers Started Replying Again

→ Part 3: Fill the Holes in 90 Seconds (Before Your Brain Talks You Out of It)

Bill gates fault. He started the spellchecker. Made spelling & grammar accessible to everyone 😜

This week I witnessed a Chat GPT agent curate some news, inject into a carousel template, create a caption which got posted on linked in saying "Sometimes the best way to cut through is be unmistakably human"

What a time to be alive. 😆