I Stole 6 Techniques From 2 Writers (Neither One Knows)

Tim Urban and Chuck Palahniuk have nothing in common. Except this.

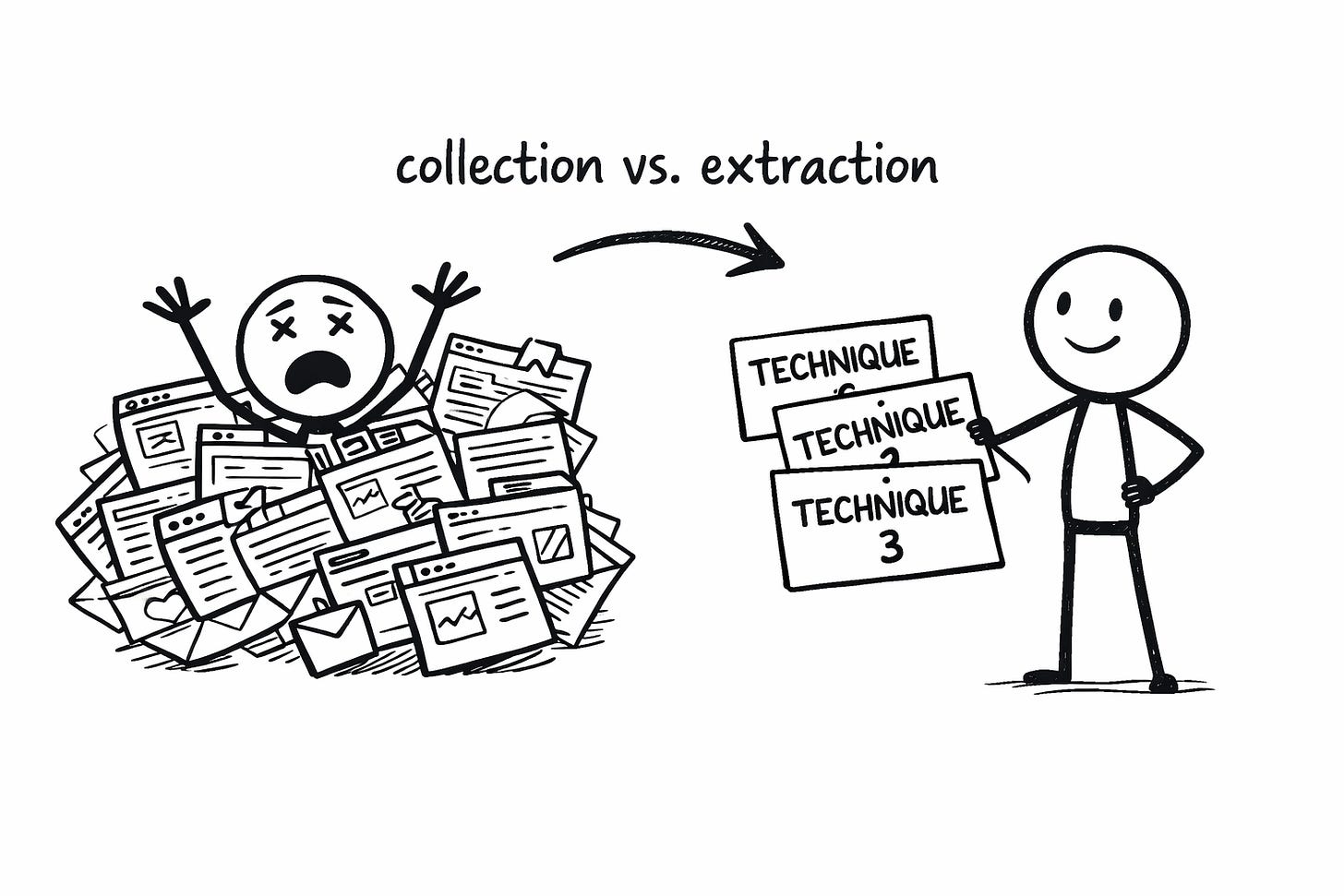

You’ve got folders. Screenshots. Bookmarks you haven’t touched since the spring equinox. A Google Doc called “inspo” that’s functionally a hospice for ambition.

None of it has made you better.

Not even a little bit.

You’ve been reading like a fan when you needed to be reading like a thief. Fans applaud. Thieves take notes. The writers you’ve bookmarked left their techniques exposed. You were too busy clapping to pick their pockets

You Can't Steal What You Can't Name

Admiration doesn’t transfer. This is the cruelest joke in creative education.

You can watch Dai Vernon’s cups and balls until your eyes cross. Slow it down. Frame by frame. Feel that same spark every time something appears that shouldn’t exist. But until someone names the mechanics (the load hidden in the lift, the misdirection baked into the patter, the steal that happens while you’re reacting to the last reveal), you can’t add any of it to your little bag of tricks. You’re just a mark who watched the show twice.

You can only applaud.

Writing works identically.

You read something magnetic and you think damn. Maybe you screenshot it. Maybe you save it to a folder we both know you’re never opening again. Maybe you tell yourself you’ll really read it later..

(You won’t. The lie is comfortable and that’s why we keep telling it.)

And even if you DO go back. Even if you read it again with your serious face on. You walk away with the exact same vague appreciation you started with.

“The writing flows well.”

“It’s engaging.”

“It just works.”

We’ve all said this. We’ve all meant it. And we’ve all walked away with nothing we could actually use.

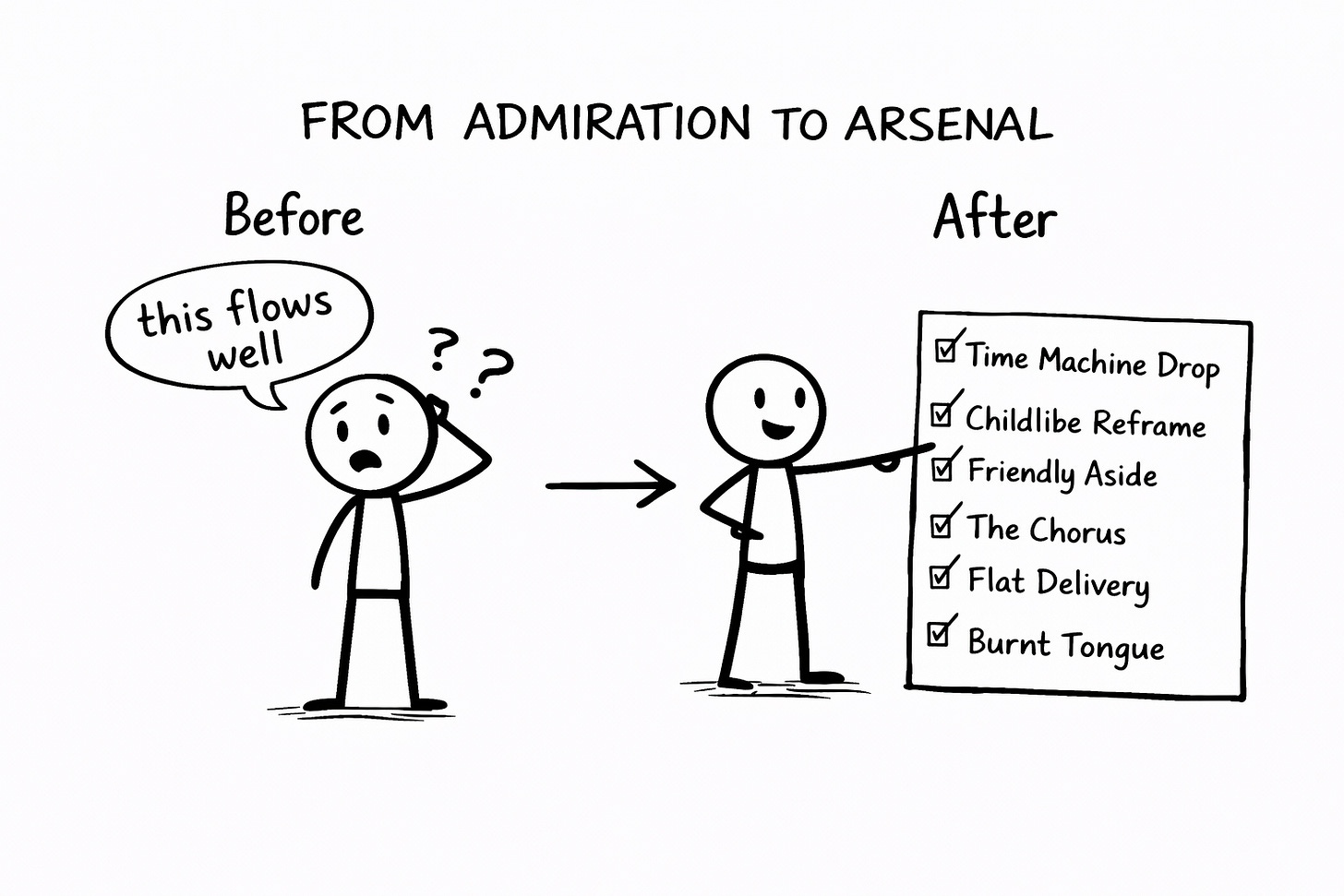

A technique you cannot name is a technique you cannot use.

The moment you can say “she’s stacking three flat statements then detonating them with an absurd analogy” instead of “her writing flows so well”... that technique becomes yours. Not borrowed. Not traced. Yours to deploy, mutate, and run through your own voice until it stops being hers and starts being something only you would do with it.

Naming converts feeling into function. Admiration into arsenal.

And I can prove it.

Two Writers. Six Techniques. Same Magic, Opposite Mechanics.

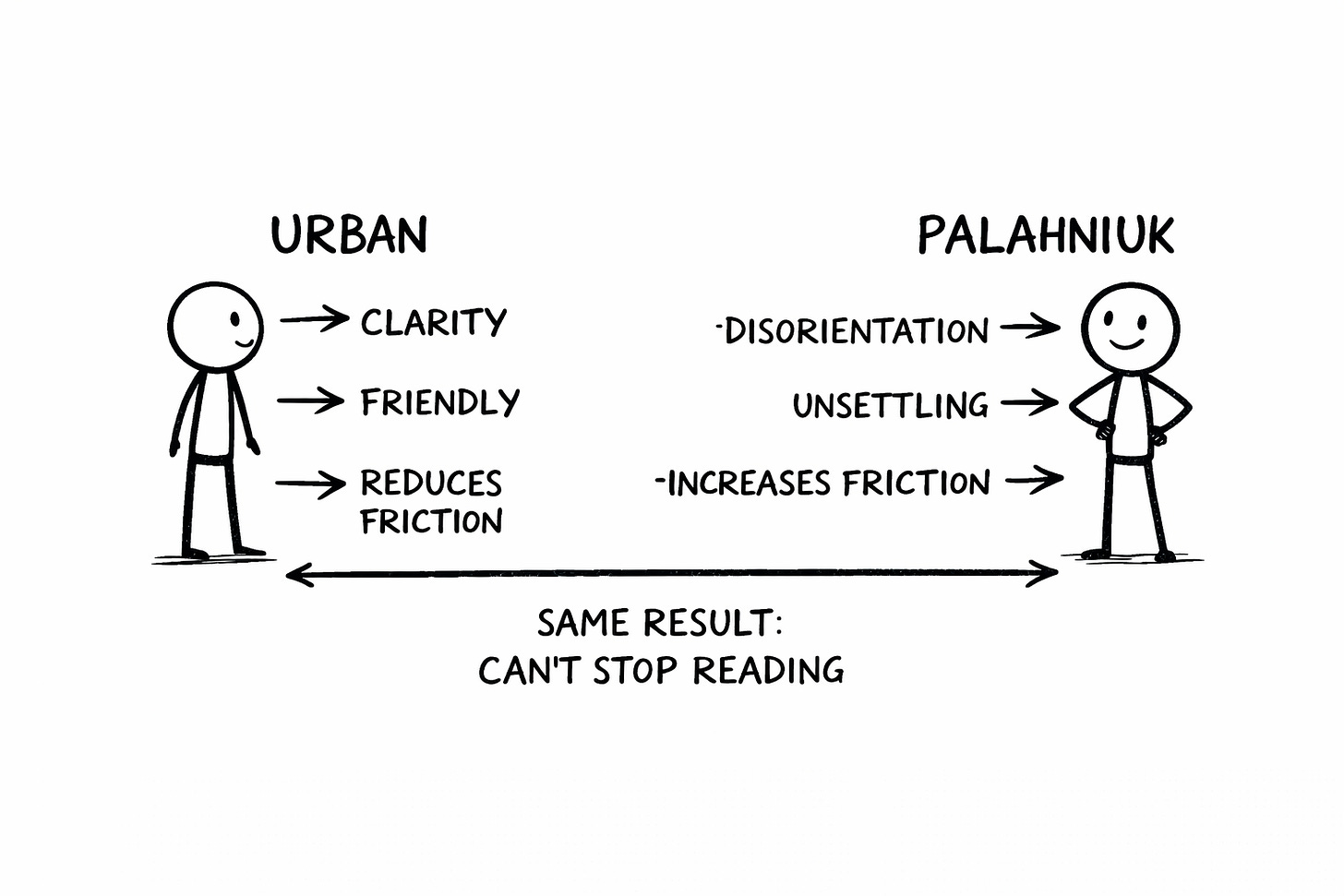

I’m about to pick the pockets of two writers you probably know. Tim Urban (Wait But Why) and Chuck Palahniuk (Fight Club, Survivor). Almost perfect opposites in every measurable way. Urban makes terrifyingly complex ideas feel like grabbing coffee with your smartest friend. Palahniuk makes ordering a sandwich feel like a fist to the sternum.

Same result. Writing you physically cannot stop reading. Completely different things worth lifting.

Watch what happens when you name what they’re doing instead of just standing there slack-jawed.

Tim Urban: The AI Revolution (Wait But Why)

Here’s a piece of content that shouldn’t work: 10,000 words about artificial superintelligence. Published in 2015, years before ChatGPT made your aunt care about AI. Dense. Technical. Posted on a blog with stick-figure drawings. (Huh. I do that. Filed under: thefts I didn’t know I committed.) Millions read it to the end. Many still reference it today.

Instead, millions of people read the whole thing. Many describe it as the piece that fundamentally rewired how they think about AI today.

A reader sees: Wow, he makes complicated stuff so easy to understand.

A namer sees three specific techniques doing the heavy lifting:

Technique 1: “The Time Machine Drop”

Urban doesn’t lead with graphs. He leads with a guy from 1750 getting dropped into the present day and asking what would happen.

The answer: the guy might literally die from shock.

Then the 1750 guy tries the same trick going backward to 1500... and the guy from 1500 is merely impressed. Not dead. Just mildly amused. Maybe asks a few questions about the fancy buttons on his jacket.

That asymmetry IS the lesson about exponential change. You felt it before you understood it. Your gut arrived at the conclusion while your brain was still parking the car.

The mechanical move: abstract concept → vivid experiential scenario → the insight arrives through empathy, not explanation. Urban doesn’t teach you that progress accelerates. He makes you watch someone’s brain liquefy from confronting it. You learn by feeling what the 1750 guy would feel.

Then (and this is the move within the move) he coins a term for it. The “Die Progress Unit.” Which is absurd. Which is sticky. Which is why you might remember it years later when you’ve forgotten every exponential curve you’ve ever seen.

The full pattern: complex idea → scenario you can feel → coined term that makes it portable.

He does this over and over. Not a party trick. The trick.

Technique 2: “The Childlike Reframe”

Urban points out that chess (the thing most humans find impossibly hard) is actually trivially easy for computers. Child’s play. Boring, even.

But recognizing when a compliment is actually an insult? Still terrible at it. Understanding why “Nice shirt” can mean three completely different things depending on who says it? Nowhere close.

The move: take the reader’s intuitive hierarchy of what’s impressive, and flip it. Prove the flip with evidence. The things you think are hard are easy. The things you think are easy are damn near impossible.

Every time Urban does this, you feel slightly smarter for having your assumption corrected. That feeling (the small dopamine hit of “oh, I was thinking about it wrong”) is what keeps you scrolling. You’re not reading for information anymore. You’re reading because your own model of the world keeps getting pleasantly disrupted.

You’re addicted to being wrong in small, manageable doses.

Technique 3: “The Friendly Aside”

Scattered throughout the piece: humanity-ending AI is called “a spicy meatball.” The article is described as having gotten “outrageously long.” The word “nahhhhh” (stretched to seven h’s) stands in for the reader’s likely skepticism.

These aren’t decoration. They’re pressure valves.

The subject matter is genuinely terrifying. Existential AI risk. Possible extinction. The end of human civilization as we know it. Light reading. Without the asides, the intensity would become unbearable. You’d close the tab to protect your nervous system.

The aside gives your brain a micro-rest. A little signal that says: the guide is still a person, not a lecturer. He also finds this overwhelming. You’re safe to keep going.

Pattern: serious concept → casual aside → return to serious.

The aside doesn’t undercut the gravity. It makes the gravity bearable. It gives you permission to keep engaging with ideas that should send you into fetal position.

Chuck Palahniuk: Survivor

Now forget everything you just learned.

(I mean it. Purge it.)

Because Palahniuk operates in almost the exact opposite direction.

Where Urban makes complex things feel simple and friendly, Palahniuk makes ordering coffee feel like a war crime. Where Urban gives you micro-rests, Palahniuk gives you micro-wounds. Where Urban reduces friction between you and ideas, Palahniuk maximizes friction between you and your comfortable assumptions about being a functional person.

Both keep you reading to the end. Urban leaves you feeling smarter. Palahniuk leaves you feeling like you need a shower.

Technique 4: “The Chorus”

Palahniuk plants a line or phrase early. Something mundane. Even boring. A cleaning tip. A brand name. A casual aside about the best way to remove blood from expensive fabric. (Household tips. Very practical. Very normal. Nothing to see here.)

Then he brings it back.

And again.

And again.

Each time, the same words. Identical phrasing. But the story has shifted around them. The context has darkened. And suddenly that cleaning tip isn’t a cleaning tip anymore. It’s the most unsettling sentence you’ve read all week.

The mechanical principle: repetition as weaponized context shift.

The words don’t change. Your understanding of them does. Each return of the chorus carries the accumulated weight of everything that happened since the last time you heard it.

Most writers avoid repetition because they were taught it’s lazy. (Their teachers were wrong about many things. This was one of them.) Palahniuk weaponizes the thing they warned you about. The repetition isn’t the technique. It’s the vehicle for the technique. What matters is choosing what to repeat.

He repeats mundane things that become sinister. The gap between the casual language and the escalating darkness IS the effect.

This is immediately extractable. Plant a phrase early. Return to it after the stakes have changed. Watch it transform without changing a single word.

Technique 5: “The Flat Delivery”

Tender Branson, the narrator of Survivor, describes telling suicidal callers to go ahead and kill themselves. Same tone he uses for getting semen stains out of expensive carpet.

No emotional markers. No “he said sadly.” No authorial hand reaching out to tell you how to feel.

This comes from a minimalist principle called “recording angel.” You describe only actions and appearances. Never tell the reader what to feel. The emotional processing happens inside the reader’s body, not on the page.

Here’s why it works: most writers telegraph emotion. They put up signs. THIS IS SAD. FEEL SOMETHING NOW. Palahniuk removes those signs entirely.

And your emotional response becomes more intense because the narrator isn’t having one.

You’re doing all the work. And because you’re doing the work, the feeling belongs to you. It’s yours. You can’t dismiss it as the author being manipulative because the author didn’t do anything. YOU felt that. You walked into that room on your own two feet.

The more disturbing the content, the flatter the delivery. That’s the rule. The contrast between what’s happening and how it’s being told IS the horror.

(And the humor. Same mechanism, different payload.)

Technique 6: “Burnt Tongue”

This one has an actual name already. Burnt tongue means deliberately saying things slightly wrong. Bending grammar. Twisting a phrase. Putting words in an order that makes you stumble.

In Survivor, Tender describes his pet: “This is fish number six hundred and forty-one in a lifetime of goldfish.”

Not “my six hundred and forty-first goldfish.” Not “I’ve had over six hundred goldfish.” The phrasing is clinical and strange, like someone learned English from an instruction manual. It forces you to re-read. You slow down. You notice.

Most polished prose is designed to be transparent. You look through the words at the meaning, like a window. Burnt tongue makes the glass visible. You notice the words themselves.

That friction creates presence.

You cannot skim Palahniuk the way you skim a blog post. The language keeps catching your foot. The floor is uneven on purpose.

(Side note for the AI-aware audience: this is the anti-slop technique. AI generates probable text. The smoothest, most expected phrasing. Burnt tongue is deliberately improbable phrasing. The exact opposite of what a language model would produce. Which is why it feels so irreducibly, stubbornly human. Nobody automated that stumble.)

The Contrast Is the Point

You finish both. You can’t skim either. Urban picks your pocket while you’re nodding along, feeling smart. Palahniuk steals your watch while you’re trying to figure out what the hell just happened.

Same grip. Different techniques. Both worth stealing.

You couldn’t have seen any of that while you were busy admiring. You needed to name it.

Your Move

Pick a writer you admire. Someone whose work makes your chest tighten. Pull one piece. A newsletter, an essay, a chapter.

Read it twice.

First read: enjoy it. Let it do its thing. Be a fan.

Second read: name one technique. One move you couldn’t have articulated before. That’s it. One is enough to change how you read everything after.The names don’t need to be clever. They need to be specific.

“Short-long-short sentence pattern” counts. “She stacks questions then answers the last one” counts. “He drops a one-word paragraph after a long buildup” counts.

“Good vibes” doesn’t count. “Engaging” doesn’t count. “Flows well” doesn’t count.

Those are feelings. You’re hunting for mechanics.

Name one technique by Friday. Use it in your next draft. See what happens.

🧉 Who’s one writer you’ve been admiring when you should’ve been stealing? Dro them in the comments. Even better: name one technique you’ve already spotted.

Crafted with love (and AI),

Nick “The Technique Thief” Quick

PS… Once you start naming other writers’ techniques, you’ll want to name your own. The Voiceprint Quick-Start Guide walks you through it. Free.

PPS… Subscribe. (Please.) Forward this to the screenshot hoarder in your life. You know who they are. They know who they are.

This is sooooo good, love it. I do this constantly with prompts now (although on a much, much simpler level haha) - I'll see someone's AI output and think damn, that's smooth, but unless I can name what pattern they're using in the prompt structure, I can't steal it.

Like when I finally gave a name to "constraint stacking" for example, I could use that move everywhere. Same with false start removal, where you make it generate twice and throw out the first attempt.

I like to think that once you name it, you own it.

I love that you're applying this to prompts. It's the same muscle. You see output that works, you name why it works, suddenly you can do it on purpose instead of hoping you catch lightning in a bottle (twice!).

"False start removal" is one I've been doing a version of for awhile without a name. Generate twice, throw out the first attempt. Now it's a technique I can teach instead of a habit I can't explain. That's the whole point of naming.

Also, "once you name it, you own it" is cleaner than anything I wrote. Stealing it back.